on fiction and Finkler.

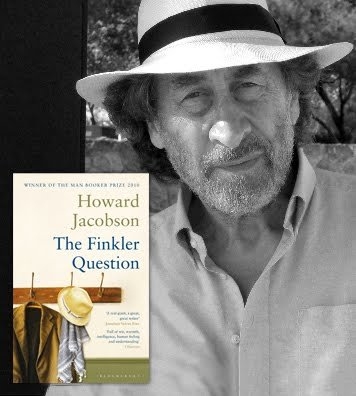

I’ve had a week or so to digest this year’s 26 Speech ‘The Art of Writing with Howard Jacobson’ at the British Library. It was a fantastic evening, buoyed by the news that Jacobson had won the Mann Booker Prize just a few days earlier. A lesser man might have shirked his earlier commitments, but despite having lost most of his voice through constant interviews and minimal sleep, the author turned in a sterling performance. So it wasn’t really a speech, more of a chat, but all the more intimate and revealing for it.

I’ve been a fan of Jacobson’s since the early 1980s, when his first book, the edgy campus romp ‘Coming From Behind’ was published. Since then, I’ve read most of his novels, most recently the fascinatingly disturbing ‘Act of Love’.

In person, he was disarmingly frank, tremendously funny and wonderfully insightful, coaxed and cajoled by the pitch-perfect interviewing of 26 Chairman Martin Clarkson. Jacobson jokingly suggested they might go on tour as a double act — which isn’t an entirely ridiculous idea.

So what did we learn? That even a successful, award-winning, crowd-pleasing writer is incredibly ‘thin skinned’ — sensitive to slights, criticism and perennially jealous of his peers. Jacobson’s tone wavered from self-mockery to bravura, so you were never quite sure where the joke stopped and the seriousness kicked in. He was certainly an entertaining speaker, his razor-sharp responses packed with memorable one liners on everything from God to sex, family to comedy.On the subject of novel writing, one of the most interesting things he said was that he has no idea what’s going to happen before he starts writing, he just lets the characters evolve and develop until they find a natural path. “Bloody plot. Who did it? Who cares? Character is plot.” There’s nothing mystical about it, he claimed, but ushering them down a preordained plotline makes the writing mechanical and contrived like forcing words into a crossword grid. This makes sense, though writing free-form like this requires tremendous skill and experience.Jacobson eschewed the description of comic novelist, though professed to writing comedy. But strictly black no sugar. “I like to find it where it shouldn’t be, where it’s either slit your wrists or laugh… My humour doesn’t tickle you, it hurts you. It’s like being forced to the ground and stabbed in the heart,” he said.

I liked what he said about character names too — that they should be curious and evocative, something Dickens always seemed to manage. “How can I possibly be interested in what happens to someone called Paul?”Anything else? Well, plenty. But for obscurists… his younger brother was in a band that went on to become 10cc, though left before they made it. Jacobson once ran a restaurant down in Cornwall with his then wife. And he used to live on the same south London street as Ian McEwan and Angela Carter.I was pleased that Clarkson used both the questions I’d supplied him verbatim:Sex is always bubbling somewhere near the surface of your novels. Do you enjoying writing about sex as much as people enjoy reading about it?You return to various themes time and time again – sex, jealousy, cuckoldry, Jewishness, embarrassment, snobbery, learning – how important is it for a novelist to have a particular set of preoccupations?And even more pleased to win a copy of ‘The Finkler Question’ for knowing the title of Jacobson’s other Booker-shortlisted novel (‘Who’s Sorry Now’). I had it signed afterwards during a slightly embarrassed chat… the inscription reads: “To Jim… who’s sorry now? Not me.”